The Romans usually treated their traditional narratives as historical, even when these have miraculous or supernatural elements. The stories are often concerned with politics and morality, and how an individual's personal integrity relates to his or her responsibility to the community or Roman state. Heroism is an important theme. When the stories illuminate Roman religious practices, they are more concerned with ritual, augury, and institutions than with theology or cosmogony.[1]

The study of Roman religion and myth is complicated by the early influence of Greek religion on the Italian peninsula during Rome's protohistory, and by the later artistic imitation of Greek literary models by Roman authors. The Romans were curiously eager to identify their own gods with those of the Greeks (see interpretatio graeca), and reinterpret stories about Greek deities under the names of their Roman counterparts.[2] Rome's early myths and legends also have a dynamic relationship with Etruscan religion, less documented than that of the Greeks.

While Roman mythology may lack a body of divine narratives as extensive as that found in Greek literature,[3] Romulus and Remus suckling the she-wolf is as famous as any image from Greek mythology except for the Trojan Horse.[4] Because Latin literature was more widely known in Europe throughout the Middle Ages and into the Renaissance, the interpretations of Greek myths by the Romans often had the greater influence on narrative and pictorial representations of "classical mythology" than Greek sources. In particular, the versions of Greek myths in Ovid's Metamorphoses, written during the reign of Augustus, came to be regarded as canonical.

Contents[hide] |

[edit] The nature of Roman myth

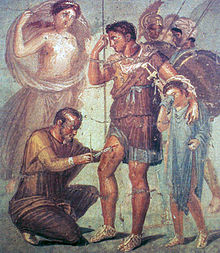

In this wall painting from Pompeii, Venus looks on while the physician Iapyx tends to the wound of her son, Aeneas; the tearful boy is her grandson Ascanius, also known as Iulus, legendary ancestor of Julius Caesar and the Julio-Claudian dynasty

The Roman stories still matter, as they mattered to Dante in 1300 and Shakespeare in 1600 and the founding fathers of the United States in 1776. What does it take to be a free citizen? Can a superpower still be a republic? How does well-meaning authority turn into murderous tyranny?[8]Major sources for Roman myth include the Aeneid of Vergil and the first few books of Livy's history. Other important sources are the Fasti of Ovid, a six-book poem structured by the Roman religious calendar, and the fourth book of elegies by Propertius. Scenes from Roman myth also appear in Roman wall painting, coins, and sculpture, particularly reliefs.

[edit] Founding myths

- Main article: Founding of Rome.

[edit] Other myths

Mucius Scaevola in the Presence of Lars Porsenna (early 1640s) by Matthias Stom

- Rape of the Sabine women, explaining the importance of the Sabines in the formation of Roman culture, and the growth of Rome through conflict and alliance.

- Numa Pompilius, the Sabine second king of Rome who consorted with the nymph Egeria and established many of Rome's legal and religious institutions.

- Servius Tullius, the sixth king of Rome, whose mysterious origins were freely mythologized and who was said to have been the lover of the goddess Fortuna.

- The Tarpeian Rock, and why it was used for the execution of traitors.

- Lucretia, whose self-sacrifice prompted the overthrow of the early Roman monarchy and led to the establishment of the Republic.

- Horatius at the bridge, on the importance of individual valor.

- Mucius Scaevola ("Lefty"), who thrust his right hand into the fire to prove his loyalty to Rome.

- Caeculus and the founding of Praeneste.[10]

- Manlius and the geese, about divine intervention at the Gallic siege of Rome.[11]

- Stories pertaining to the Nonae Caprotinae and Poplifugia festivals.[12]

- Coriolanus, a story of politics and morality.

- The Etruscan city of Corythus as the "cradle" of Trojan and Italian civilization.[13]

- The arrival of the Great Mother (Cybele) in Rome.[14]

[edit] Religion and myth

| Ancient Roman religion |

Marcus Aurelius (head covered) Marcus Aurelius (head covered)sacrificing at the Temple of Jupiter |

| Practices and beliefs Imperial cult · festivals · ludimystery religions · funerals temples · auspice · sacrifice votum · libation · lectisternium |

| Priesthoods College of Pontiffs · AugurVestal Virgins · Flamen · Fetial Epulones · Arval Brethren Quindecimviri sacris faciundis |

| Jupiter · Juno · Neptune · Minerva Mars · Venus · Apollo · Diana Vulcan · Vesta · Mercury · Ceres |

| Other deities Janus · Quirinus · Saturn ·Hercules · Faunus · Priapus Liber · Bona Dea · Ops Chthonic deities: Proserpina · Dis Pater · Orcus · Di Manes Domestic and local deities: Lares · Di Penates · Genius Hellenistic deities: Sol Invictus · Magna Mater · Isis · Mithras Deified emperors: Divus Julius · Divus Augustus See also List of Roman deities |

| Related topics Roman mythologyGlossary of ancient Roman religion Religion in ancient Greece Etruscan religion Gallo-Roman religion Decline of Hellenistic polytheism |

Main article: Religion in ancient Rome

Divine narrative played a more important role in the system of Greek religious belief than among the Romans, for whom ritual and cult were primary. Although Roman religion was not based on scriptures and exegesis, priestly literature was one of the earliest written forms of Latin prose.[15] The books (libri) and commentaries (commentarii) of the College of Pontiffs and of the augurs contained religious procedures, prayers, and rulings and opinions on points of religious law.[16] Although at least some of this archived material was available for consultation by the Roman senate, it was often occultum genus litterarum,[17] an arcane form of literature to which by definition only priests had access.[18] Prophecies pertaining to world history and Rome's destiny turn up fortuitously at critical junctures in history, discovered suddenly in the nebulous Sibylline books, which according to legend were purchased by Tarquin the Proud in the late 6th century BC from the Cumaean Sibyl. Some aspects of archaic Roman religion were preserved by the lost theological works of the 1st-century BC scholar Varro, known through other classical and Christian authors.At the head of the earliest pantheon were the so-called Archaic Triad of Jupiter, Mars, and Quirinus, whose flamens were of the highest order, and Janus and Vesta. According to tradition, the founder of Roman religion was Numa Pompilius, the Sabine second king of Rome, who was believed to have had as his consort and adviser a Roman goddess or nymph of fountains and prophecy, Egeria. The Etruscan-influenced Capitoline Triad of Jupiter, Juno and Minerva later became central to official religion, replacing the Archaic Triad — an unusual example within Indo-European religion of a supreme triad formed of two female deities and only one male. The cult of Diana was established on the Aventine Hill, but the most famous Roman manifestation of this goddess may be Diana Nemorensis, owing to the attention paid to her cult by J.G. Frazer in the mythographical classic The Golden Bough.

The gods represented distinctly the practical needs of daily life, and they were scrupulously accorded the rites and offerings considered proper. Early Roman divinities included a host of "specialist gods" whose names were invoked in the carrying out of various specific activities. Fragments of old ritual accompanying such acts as plowing or sowing reveal that at every stage of the operation a separate deity was invoked, the name of each deity being regularly derived from the verb for the operation. Tutelary deities were particularly important in ancient Rome.

Thus, Janus and Vesta guarded the door and hearth, the Lares protected the field and house, Pales the pasture, Saturn the sowing, Ceres the growth of the grain, Pomona the fruit, and Consus and Ops the harvest. Even the majestic Jupiter, the ruler of the gods, was honored for the aid his rains might give to the farms and vineyards. In his more encompassing character he was considered, through his weapon of lightning, the director of human activity and, by his widespread domain, the protector of the Romans in their military activities beyond the borders of their own community. Prominent in early times were the gods Mars and Quirinus, who were often identified with each other. Mars was a god of war; he was honored in March and October. Quirinus is thought by modern scholars to have been the patron of the armed community in time of peace.

The 19th-century scholar Georg Wissowa[19] thought that the Romans distinguished two classes of gods, the di indigetes and the di novensides or novensiles: the indigetes were the original gods of the Roman state, their names and nature indicated by the titles of the earliest priests and by the fixed festivals of the calendar, with 30 such gods honored by special festivals; the novensides were later divinities whose cults were introduced to the city in the historical period, usually at a known date and in response to a specific crisis or felt need. Arnaldo Momigliano and others, however, have argued that this distinction cannot be maintained.[20] During the war with Hannibal, any distinction between "indigenous" and "immigrant" gods begins to fade, and the Romans embraced diverse gods from various cultures as a sign of strength and universal divine favor.[21]

[edit] Foreign gods

Mithras in a Roman wall painting

In some instances, deities of an enemy power were formally invited through the ritual of evocatio to take up their abode in new sanctuaries at Rome.

Communities of foreigners (peregrini) and former slaves (libertini) continued their own religious practices within the city. In this way Mithras came to Rome and his popularity within the Roman army spread his cult as far afield as Roman Britain. The important Roman deities were eventually identified with the more anthropomorphic Greek gods and goddesses, and assumed many of their attributes and myths.

[edit] Sources

- Alan Cameron Greek Mythography in the Roman World (2005) OUP, Oxford (reviewed by T P Wiseman in Times Literary Supplement 13 May 2005 page 29)

- Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae (LIMC) (1981–1999) Artemis-Verlag, 9 volumes.

No comments:

Post a Comment